Shan Goshorn (1957 - 2018)

Eastern Band Cherokee artist Shan Goshorn lived in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Her work has been exhibited extensively in the United States and is part of prestigious collections such as the National Museum of the American Indian (Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC), the Surgut Museum of Art in Russia and the Nordamerika Native Museum in Switzerland.

Shan Goshorn has received the 2015 United States Artist Fellowship, 2014 Natives Arts and Culture Artist Fellowship, 2013 Eiteljorg Contemporary Art Fellowship, the 2013 Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship and the 2013 SWAIA Discovery Fellowship.

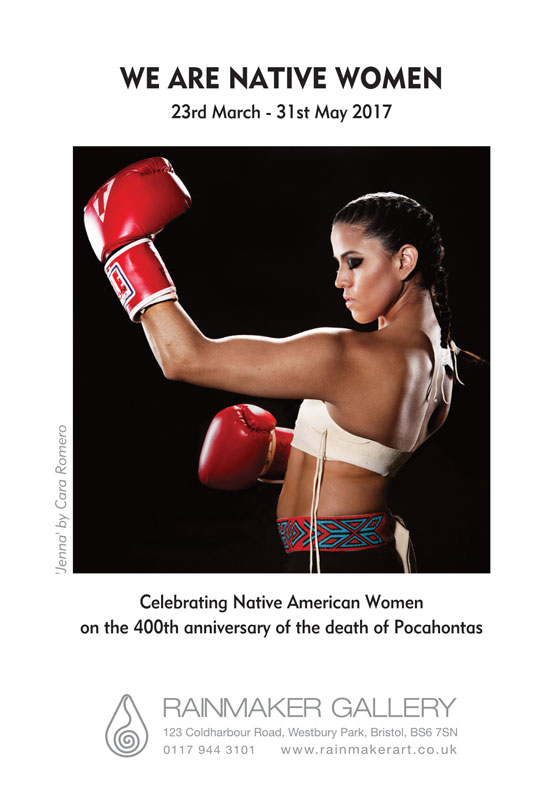

Shan Goshorn was one of twelve artists selected for the We Are Native Women exhibition marking the 400th anniversary of the death of Pocahontas. The following three artworks and accompanying text were included in the exhibition along with the artist statement ‘Not Your Pocahontas’ below.

Viable I

“It is the mothers not the warriors, who create a people and guide their destiny.” Luther Standing Bear

“The digital composite, Viable, uses Luther Standing Bear’s words as the backdrop for a photo portrait series featuring a young Indian woman (Jasha), carrying our most precious cultural legacy. This image sends a literal message – one about her gestation of a cherished gift – but also metaphorically, that as Indigenous people, we have a responsibility to nurture and keep our culture alive.” SG

Warrior Bloodline series:

“Inspired by my research in the archives of the Smithsonian Institution (Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship, 2013), this set of ten baskets is an homage piece to celebrate the strength and courage of native women. While viewing studio portraits of native people in the museum’s archives, it became quickly obvious that most of the portraits featured men; the few women were identified as if they were the chattel of men, i.e. “Squaw of Spotted Tail” or “Little Soldier’s Squaw.” The viewer should understand that the term “squaw” is not a favorable one but rather the Algonquin word for vagina- indicating the white newcomer’s perceived use or value of Indian women. I felt fiercely that these beautiful, strong women, who were representative of a variety of Indigenous nations, deserved recognition and honor beyond these labels. I wanted to illustrate how they personify the passion of our tribes, tending the fires of tradition and fueling the flames of perseverance.

I also wanted to recognize extraordinary women of all tribes both past and present. I made an online request for the names of native women who have collectively inspired and strengthened us; within 48 hours, I received over 700 names. These names have been woven into the interior of the baskets to honor women who have shaped our lives in some way.

The impact these women have had on native communities and the feminine influence that will continue to inspire future generations is undeniable. This critical guiding force is summed up in the quote by Oglala Lakota, Luther Standing Bear, which is wrapped on the interior and exterior basket rims: It is the mothers, not the warriors, who create a people and guide their destiny. ”

SG

Wa-Hu-Wa-Pa or Va-How-A-Pah (Ear of Corn)

Oglala, Wife of Lone Wolf

Photographer: Alexander Gardner 1872, photographed in Washington DC during delegation visit from Pine Ridge, NAA Collection.

Mik-Tekhe

Omaha, age 13

Also called Lune Dure, French for “lasting moon” or “hard moon”

Photographer: Prince Roland Bonaparte 1880’s, NAA Collection

Artist Statement: Not Your Pocahontas

“Native women, both past and present, have traditionally been respected and honored within tribes not only for their roles as mothers and caregivers but also for their roles in positions of spiritual power, tribal relations, governance and even warfare. Indigenous women have been and are still today integral in advancing our culture, maintaining our traditions and strengthening our unity and resolve in the midst of great hardship.

Nonetheless, when one Googles “Native American woman,” there are countless inappropriate images of women (of all races) wearing face paint, erotic costumes comprised of buckskin, feathers and beads. And always, there is the cartoon image of Pocahontas.

The Pocahontas story is one that is told many different ways, but always by others, never a first person family account and rarely by a native person. Audiences seem fascinated with the dominant society’s version of the retelling because in it, Pocahontas is the good Indian, the beautiful Indian maiden who saves the life of a white man because she is desperately in love with him. Hollywood has put a powerful PR spin on an animation that perpetuates the myth of a scantily clad Indian princess who is ready to throw aside all tribal traditions to embrace her white man hero, and thus his white culture.

In truth, Pocahontas was kidnapped against her will and used as a pawn by her captors to negotiate trade agreements with her tribe and to create positive European publicity for the colonies. Mindful of her tribal status and obligations to her people, this brave young woman exhibited great skill in navigating an alien culture and sacrificing her freedom to serve as an unintentional ambassador between two people during her short life. But until the world acknowledges the ugly truth behind this myth, the accomplishments of many other extraordinary native women who deserve recognition and remembrance will go unnoticed; distorted stereotypes like this one will continue to obscure any attempt at desired understanding between cultures.

Dooming a person’s existence to that of a stereotype is worse than never having lived at all. It is ridiculously past time for us to rewrite the past with the truth.” SG